A recent advertisement for a Bank of Palestine savings scheme, reproduced on billboards and in magazines all over the Ramallah-al-Bireh-Beitounia conurbation (hereafter Ramallah), tells residents “Together We Are a Family.” We are clearly meant to think that the Bank of Palestine wants, or considers itself, to be part of the family. Although counterintuitive, this proposition embodies the ways in which banks have become increasingly part of intimate urban life in the central city of the occupied West Bank. This is not least because residents owe increasingly large sums of money to those banks. In this essay I chart the ways financial debt has proliferated in Ramallah. But I also want to caution against accounts that narrate this expansion as an all-conquering force that sweeps away all social ties it comes into contact with.

Palestinian Monetary Authority (PMA) statistics tells us that as of July 2014 the Palestinian Authority (PA) owes almost 2.4 billion dollars to various others, of which approximately 1.25 billion dollars is owed to banks in Palestine. Meanwhile Palestinian “consumers” are indebted to the tune of 430 million dollars for housing loans, 123 million for vehicle financing, and 889 million for consumption loans, or 1.442 billion dollars in total. This figure represents an almost six fold increase since 2008, although it is also worth noting that the rate of increase was greatest between 2009 and 2012, and slowed considerably in 2013. While these figures represent the whole of the West Bank, two-thirds of all credit is held in Ramallah. Like many other things, debt is concentrated in the West Bank’s central city.

The reasons for the concentration of certain aspects of Palestinian life in Ramallah are well understood and documented (Taraki 2008, Abourahme 2009, Rabie 2013). The division of the West Bank into areas A, B and C during the Oslo Accords, the centralization of the PA ministries in Ramallah because they could not be located in Jerusalem, the massive intensification of movement restrictions across the West Bank, and the disconnection of northern cities from their hinterlands by the barrier wall, have all contributed to high levels of internal migration from other parts of the West Bank to Ramallah after 2003. These migrants arrived in a conurbation which has long been considered “open,” the very growth of which has largely been the result of immigration from various other places, not least refugees who came from coastal cities during and after 1948. For recent migrants who do not own land but want to live in Ramallah, debt has become a key means through which to gain a residential foothold in a city often characterized as “modern,” an understanding related to the consumption of commodities, culture, and education (Taraki 2008). In Um-Asharayet—a neighborhood sometimes described as lower-middle class and other times “popular,” where I am conducting a research project with Reema Shebeitah and Dareen Sayyad—residents have taken loans to buy apartments and cars, to pay for daily, travel, medical and wedding expenses, to furnish or renovate their homes, and to improve private businesses.

Debt as Governance

In addition to rising demand and prices, the growth of privately held debt in Ramallah can also be traced to the increased provision of financial credit. Banks provided increased credit as a capital accumulation strategy in response to new Palestinian Monetary Authority (PMA) regulations in 2008-9 limiting the percentage of deposits banks could move (and invest) abroad. The introduction of a “national” (public) credit registry by the PMA in 2007 also facilitated such changes. Given the ongoing political instability in Palestine, banks have targeted what they define as the lowest risk sectors: housing and services. Journalists Amira Hass and Dalia Haquta suggest that the debt-fuelled consumption that has subsequently emerged can be read as a kind of economic peace initiative, a form of pacification that replaces communal political struggles for future national liberation with the promise of a present-day good life, as defined by capitalism. Consumption-fuelled economic development in the West Bank fits squarely alongside the myriad ways in which the Israeli Occupation materially impoverishes Palestinians. This includes the closure regime that is largely responsible for high levels of internal migration to Ramallah (which has driven up demand for housing and land prices). This impoverishment also entails the de-development of Palestinian productive capacity through a range of processes including land theft, building restrictions, lack of border control, and movement restrictions on goods and people. Historically, there have also been a number of efforts to mitigate or circumvent the effects of occupation through economic development. Gordon (2008) documents such processes, including agricultural development programs and the incorporation of at least forty percent of the Palestinian working age population in the Israeli labor market, during the first twenty years of Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza Strip. Current attempts at economic development differ in that they emerge as a legacy of the Oslo Accords, and the specific geography and style of colonial governance that the Accords instantiated, which is to say an assemblage that now includes the PA, international donors, and NGOs alongside Israel. Nevertheless, PMA policies that have induced Palestinian banks to loan more money resonate with a series of governance practices that have a longer genealogy. Whether intentional or not, such practices shape the conduct of the Palestinian population (rather than disciplining their bodies). Banks position Palestinians as consumers, who choose to take loans of their own ‘free’ will (even though such an assumption lacks any credibility in a society under Occupation). Once indebted, these new consumers are then obliged to repay the banks through continued participation in the labor force. Given low rates of pay, this can mean many years of working the equivalent of two days a week for the bank (since banks can by law deduct up to forty percent of an individual’s salary upon deposit for debt repayment).

Debts, Obligations, and Everyday Life

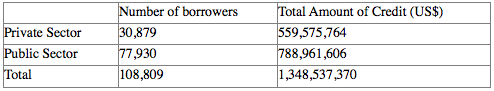

Contrary to widely circulating rumors in Ramallah that ninety percent of people or employees now have bank loans, figures provided by the PMA (see table 1) indicate that as of 1 July 2014, only four percent of the working-aged population in the West Bank and Gaza Strip have taken a bank loan, or thirty-eight percent of all public sector employees.

Table 1. Credit/debt sold to individuals by banks in the West Bank and Gaza. (Source: The Palestinian Monetary Authority, 2014)

Although almost impossible to enumerate, it is probable that non-bank credit/debt is much more extensive. In Um-Asharayet, the creditors to whom money is owed are quite diverse. In addition to banks, loans are also taken from family members, friends, work colleagues, employers in the form of a salary advance or via company loan schemes, traders in the form of post-dated checks, and building owners in the form of installment payments for an apartment. Such extensive debt-related ties might explain the rumors about high levels of bank debt. These ties also enable debt, like other obligations, to be viewed through the social practices and intimate spaces of everyday life.

Like the Bank of Palestine advert mentioned at the beginning of this essay, many participants in our research think about the intimacy of family life in relation to banks and debt. One participant even quipped that a friend who had taken a bank loan to get married would have to give his wife to the bank if he couldn’t repay the loan. This joke points to the way financial debt has been inserted into longer established social practices, in this case getting married. Another example would be wedding attendance, a common practice for many residents of Um-Asharayet who attend multiple weddings each weekend in the summer. This can amount to a significant expense, particularly if it involves travelling long distances, buying clothes, and above all because guests are obliged to contribute a cash-gift (or sometimes gold in the case of close relatives). We have documented instances where taking a consumer loan enables such gift giving. However, debt repayment more often prevents—albeit indirectly—rather than enables the fulfillment of social commitments. We heard numerous stories where residents did not attend weddings because they did not have the money for the financial gift.

Listening to stories of living with debt, it is clear that rather than the promised good life, bank debt experienced in the present tense is an obligation to pay up now, and this in turn forces the sacrifice or deferment of other forms of (social) life to the future. The harm that financial debt often enacts is chronic and ongoing rather than periodic and eventful. What this means is that it is hard to point to particular moments of violence, since debt’s temporality is precisely not momentary. Similarly, debt’s relational nature makes it hard to locate in a particular space. However, debt’s violence is discernible in the wearing down and wearing away of life. People struggle—working long(er) hours and/or more than one job—to generate enough income to simultaneously honor their social commitments and repay their debts to banks. Many residents say that the necessity of working long hours sidelines other activities, such as resistance to the Israeli occupation. This is hard to determine empirically, and it may be the case that rather than de-politicization, the suffering occasioned by indebtedness in fact contributes to new forms of political discontent associated with growing inequality and authoritarianism within Palestinian society. What our research does show is that migrant families become more spatially confined to Ramallah as the cost of visiting relatives elsewhere becomes harder to meet, potentially weakening the ties that bind people and places throughout the West Bank. For instance, Nasser, a public sector employee in his fifties from Tubas, told us that his brother who still lives in Tubas now represents the whole family at social occasions in the village in which he grew up. While Nasser visits his two brothers and nephew who also live in Ramallah every day, he only returns to his village every six months, usually for feasts (Eid). Part of the reason he does not visit Tubas more regularly is cost. He is currently making 1,200 dollars monthly mortgage repayments, (which drop to 850 dollars after two years), for the next nineteen years. Consequently:

The relationship with the extended family is weaker than the relationships with the nuclear family. There are many difficulties now. All the conditions have changed. Everyone has their own work, and their own problems. And they are busy with these issues. They have no time to go and visit, to sit and talk. This is common. It’s not just myself. (Interview with Nasser, 6 June 2013)

Nevertheless, to suggest that social life is always and everywhere overridden and restructured by financial debt would be simplistic and reductive. For instance non-attendance at social obligations often happens because of a range of factors, including not having enough time, having other social commitments, being ill, or not wanting to go. These can only be linked with indebtedness in some instances. Furthermore, for some participants it literally seemed almost unthinkable to miss a social occasion, regardless of their finances. Many affirmed the importance of social life and values, such as mutuality, over the capitalist values underpinning bank debt, such as personal benefit. Nor does capitalist value map on to the values underpinning social life in any straightforward manner, which is not to say that they are unrelated.

In Um-Asharayet, the multiple ways in which residents owe things to others creates a space of social, which is to say political, contestation—if we understand politics to be the ways in which the problems of living together are worked through and worked out. This space is dynamic and changing, but it would be wrong to assume that there is some sort of teleological end point. While Israeli and PA elites and international donor states have a very great capacity to act in this context, residents such as those in Um-Asharayet we have talked with also shape the current state of affairs by circulating ideas about the enduring and renewed importance of social ties and commitments, including their importance over financial obligations. As Waleed contends, “Social obligations are the basic obligations and financial obligations are just a means to facilitate social life.” Residents also develop or reinforce economic relations in ways that bypass banks through personal agreements with traders and building owners. We also encountered acts of personal austerity where residents refused to live a consumption-driven lifestyle. Rami told us, ‘It is not important for me to possess everything that my friend or neighbor owns. I guess satisfaction with your personal financial situation is an important aspect in the process of acclimatization. Loans provide temporary luxury.” During our research there were also multiple examples of improvisation, where residents used what was at hand—such as the urban environment—to enable social life at little to no cost (e.g. a wedding lunch in a parking garage).

Often such ideas and practices are far less visible than adverts for the Bank of Palestine, and in some cases actively seek invisibility. Hence the potency of such acts may seem negligible in the face of the power of the PA-businessmen-donor consensus. However, as Elizabeth Povinelli (2011: 78) reminds us, “The social worlds of the impractical and disagreeable remain in durative time. They persist. But do not persist in the abstract.” Put another way, while living with debt might be seen as a sacrificial good (i.e. suffer now, benefit later) from the perspective of dominant worlds, or as a state of limbo by critical scholarly communities, those who live in such a situation are by necessity problem solvers, constantly working away at how to endure and move beyond such conditions. One of the key challenges in contemporary Ramallah is how to support and disseminate such practices of endurance and invention.

References

Abourahme, Nasser. “The Bantustan Sublime: Reframing the Colonial in Ramallah.” City 13, 4 (2009): 499-509. Gordon, Neve. Israel’s Occupation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Povinelli, Elizabeth. Economies of Abandonment. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Taraki, Lisa. “Urban Modernity on the Periphery: A New Middle Class Reinvents the Palestinian City.” Social Text 26, 2 95 (2008): 61-81.